5.10.17 | UW–Madison News | David Tenenbaum | Original Publication

Whether you are tagging a photo in Facebook, asking Siri for directions to an eatery, or translating French into English, much of the action happens far from your phone or laptop, in a data center. These warehouses, each holding thousands of computers, are expanding quickly, and they already consume an estimated 2 percent of the national electricity supply.

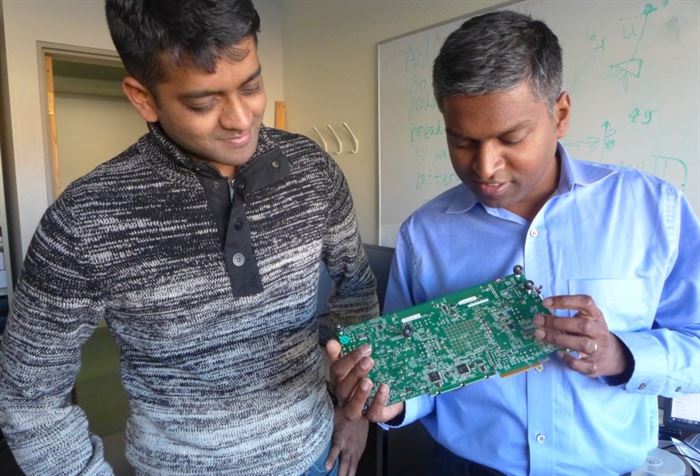

Karu Sankaralingam, a University of Wisconsin–Madison associate professor of computer science, has formed a startup to advance a streamlined chip design that will run up to 10 times faster than those now inside data centers.

SimpleMachines Inc. (SMI) has closed an over-subscribed round of seed funding, sending a strong sign that investors see merit in its streamlined approach, Sankaralingam says. “Existing server chips have been designed for various types of functions, but not all of these functions are necessary to run the range of data-center operations,” Sankaralingam says.

By stripping out unnecessary functions, and other tactics, the chips will use less electricity, reducing the need for energy to cool vast rooms full of servers.

Many of the benefits stem from a radical slowing of the chip’s “clock speed,” the potential number of calculations performed per second. Although little noticed outside the industry, there’s a growing disparity between the high-speed processors and slower memory units that feed them data. As a result, processers often must sit idle for 300 cycles or more, waiting for data.

Why buy speed you don’t need? Sankaralingam asks. “If you step back and think about what a data center requires, why not build a processor that’s much slower, so you don’t waste so many clock cycles?”

The cores in SMI’s design are only 5 to 10 percent as fast as data-center standards. Each core is only about 1 percent as big, which allows them to sit closer to the memory units that supply data.

This proximity, combined with the greater number of cores, translates into better overall speed, which helps explain the paradox of a chip that is both slower and faster.

The slower cores require far less power, and create less waste heat, which combine to slash electricity consumption.

Two UW–Madison initiatives have aided SMI:

- The Accelerator program at the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation funded the technical proof of concept, and

- University’s Discovery to Product program helped to shape its marketing strategy.

“Karu is one of the rare high-level scientists who quickly and intuitively grasps business concepts,” says John Biondi, director of D2P. “We helped Karu shape his go-to-market strategy but he is a very quick study who needed minimal help. His success in funding is due both to his technical accomplishments and his ability to put them in the right business context.”

“This is an excellent example of how entrepreneurial faculty can team with WARF and other campus resources like D2P to advance their discoveries, license them and grow a business enterprise,” says Erik Iverson, managing director of WARF. “We look forward to advancing more UW–Madison faculty startups in the years to come.”

Sankaralingam says he’s got some advantages up his sleeve. “I have been working in this area since my Ph.D. work, and believe that over the years we have distilled a mechanism to satisfy the simplest set of functions, while still having the ability to run many applications.”

Sankaralingam’s fellow co-founder is Jeff Thomas, who was a vice-president at Sun Microsystems. Graduate students Vijay Thiruvengadam, Vinay Gangadhar, and Tony Nowatzki are also involved in the project.

SMI has filed one such patent through WARF, and is exploring several more filings.

Today’s data centers run on a single type of chip, which may not be very different from what’s inside a laptop, Sankaralingam says. As data centers need to grow, competing firms are offering updated chip designs that would require data centers to use an array of different, specialized chips.

The SMI design is based on a rethinking of the problem, Sankaralingam says. “We started by asking, ‘What does transistor technology offer, and what do the applications need to do?’

“The next generation of server is typically based on modest changes to the previous rendition, but the result is a lot of clutter, unnecessary features,” he adds. “We started with a clean slate, which is a better way to build the next chip, and we wrote the design from the ground up.”

SMI’s sales pitch focuses on simplicity, Sankaralingam says. “We claim, ‘Here is one chip that provides the performance of many different chips.’ This is what any server manufacturer or data center provider says they want: One chip with all the functions they need, and nothing more.”

In SMI’s design, “We think we have struck the right balance between supporting enough general programmability to solve more problems, while being an order of magnitude better in performance,” Sankaralingam says.