3.14.19 | UW-Madison News | David Tenenbaum | Original Publication

The mother of invention visited Nicholas Von Bergen while he was caring for a newborn in the pediatric intensive care unit at American Family Children’s Hospital.

Without the recent heart surgery, the infant faced a grim future, or no future at all.

The surgery was so extensive that an organ that usually has delicate control over its rhythm may slide into a strange, unhealthy cadence. But the surgeons had attached two wires to the heart in case Von Bergen, a specialist in the heart’s pacemaking, needed to connect an external pacemaker to combat arrhythmia.

Von Bergen, an associate professor of cardiology with an emphasis on abnormal heart rhythms in children, wanted a better way to monitor heart rhythm. Knowing that the best signal was available from the new wires, he attached them to an electrocardiogram (ECG) instrument that was wheeled into the ICU for the occasion.

Though not the most elegant system, the hookup worked, showing the heart rhythm much more clearly than external leads could. But in the pediatric ICU, where everything is crowded, expensive, high-tech and high-stakes, Von Bergen thought, “Why in the world don’t we have a simple device that would allow continuous monitoring of the atria [top chambers of the heart] through these leads, which is the gold standard for arrhythmia identification?”

Today, a two-year-old startup called Atrility is moving that idea for a three-way connector toward the marketplace.

The design was begun by students in UW-Madison’s department of biomedical engineering. Doctors and others in the community can propose projects with real-world utility and financial potential to the seven-semester design class.

As the students moved ahead, Von Bergen contacted his old acquaintance Peter Lukszys, a senior lecturer in the Wisconsin School of Business, regarding the potential for a start-up business.

“My background is in big pharma, biotech, and a lot of times,” Lukszys says, “they don’t feel that a market like pediatric cardiology is big enough; these are huge companies with lots of overhead to cover.”

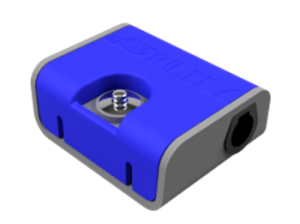

Atrility’s first device, now being prepared for production, is a three-way hub connecting wires from the heart to a bedside monitor and an external pacemaker to correct arrhythmia. The connector does not change the surgeon’s practice – a big aid to adoption.

“Usually these wires are wound up and taped to the chest,” Lukszys says, “but they hold really good information, since they have a strong atrial signal, and we can see exactly what it’s doing.”

In current practice, the information is not continuous, as each time it’s needed, an electrocardiogram technician must be summoned to hook the wires up to an ECG machine. “That takes 10 minutes, and we get a 10-second tracing and the technician leaves,” Von Bergen says. “If I make a change in treatment and want know how it went, I have to wait another 10 minutes.”

What could be merely an inconvenience can become a pressing medical issue, Von Bergen says, after extensive heart surgery often performed within a week of birth.

A patent for the invention has been filed by Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and licensed to Atrility. The big hurdle now is the steady grind toward FDA approval as a class II medical device, Lukszys says.

There are plenty more ideas where this came from, says Von Bergen, who slots nicely within the Midwestern tradition of inventors – think Cyrus McCormick (reaper) or John Deere (plow) who saw a need, invented a product, and built a company. “When I’m at work, I like to think about how we can do things better,” Von Bergen says. “If the hurdle is, ‘We have not done it yet,’ as opposed to, ‘It can’t be done,’ I say let’s do it. We want Atrility to be a home for great ideas and want to partner with others in the medical field.”